Cuba

Republic of Cuba República de Cuba (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Patria o Muerte, Venceremos ("Homeland or Death, We Shall Overcome!")[1] | |

| Anthem: La Bayamesa ("The Bayamo Song")[2] | |

Cuba, shown in dark green | |

| Capital and largest city | Havana 23°8′N 82°23′W / 23.133°N 82.383°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Other spoken languages | Haitian Creole English Lucumí Galician Corsican |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion (2020)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Cuban |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic[5][6] |

| Miguel Díaz-Canel | |

| Salvador Valdés Mesa | |

| Manuel Marrero Cruz | |

| Esteban Lazo Hernández | |

| Legislature | National Assembly of People's Power |

| Independence from Spain and the United States | |

| 10 October 1868 | |

| 24 February 1895 | |

• Recognized (Handed over to the United States from Spain) | 10 December 1898 |

• Republic declared (Independence from United States) | 20 May 1902 |

| 26 July 1953 – 1 January 1959 | |

| 10 April 2019 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 110,860[7] km2 (42,800 sq mi) (104th) |

• Water (%) | 0.94 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2022 census | |

• Density | 90.7/km2 (234.9/sq mi) (80th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

• Total | $254.865 billion[11] |

• Per capita | $22,237[11][12] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2000) | 38.0[14] medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (85th) |

| Currency | Cuban peso (CUP) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (CST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (CDT) |

| Calling code | +53 |

| ISO 3166 code | CU |

| Internet TLD | .cu |

Cuba,[c] officially the Republic of Cuba,[d] is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the northern Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean meet. Cuba is located east of the Yucatán Peninsula (Mexico), south of both Florida and the Bahamas, west of Hispaniola (Haiti/Dominican Republic), and north of Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. Havana is the largest city and capital. Cuba is the third-most populous country in the Caribbean after Haiti and the Dominican Republic, with about 10 million inhabitants. It is the largest country in the Caribbean by area.

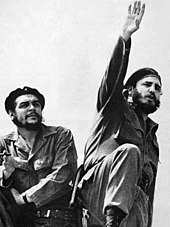

The territory that is now Cuba was inhabited as early as the 4th millennium BC, with the Guanahatabey and Taíno peoples inhabiting the area at the time of Spanish colonization in the 15th century. It was then a colony of Spain, through the abolition of slavery in 1886, until the Spanish–American War of 1898, when Cuba was occupied by the United States and gained independence in 1902. In 1940, Cuba implemented a new constitution, but mounting political unrest culminated in the 1952 Cuban coup d'état and the subsequent dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. The Batista government was overthrown in January 1959 by the 26th of July Movement during the Cuban Revolution. That revolution established communist rule under the leadership of Fidel Castro. The country was a point of contention during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States, and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 is widely considered the closest the Cold War came to escalating into nuclear war. During the 1970s, Fidel Castro dispatched tens of thousands of troops in support of Marxist governments in Africa. According to a CIA declassified report, Cuba received $33 billion in Soviet aid by 1984. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Cuba faced a severe economic downturn in the 1990s, known as the Special Period. In 2008, Fidel Castro retired after 49 years; Raúl Castro was elected his successor. Raúl Castro retired as president in 2018 and Miguel Díaz-Canel was elected president by the National Assembly following parliamentary elections. Raúl Castro retired as First Secretary of the Communist Party in 2021 and Díaz-Canel was elected.

Cuba is a socialist state, in which the role of the Communist Party is enshrined in the Constitution. Cuba has an authoritarian government where political opposition is not permitted.[16][17] Censorship is extensive and independent journalism is repressed;[18][19][20] Reporters Without Borders has characterized Cuba as one of the worst countries for press freedom.[21][20] Culturally, Cuba is considered part of Latin America.[22] Cuba is a founding member of the United Nations, G77, Non-Aligned Movement, Organisation of African, Caribbean and Pacific States, ALBA, and Organization of American States. It has one of the world's few planned economies, and its economy is dominated by tourism and the exports of skilled labor, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. Cuba has historically—before and during communist rule—performed better than other countries in the region on several socioeconomic indicators, such as literacy,[23][24] infant mortality and life expectancy. Cuba has a universal health care system which provides free medical treatment to all Cuban citizens,[25][26] although challenges include low salaries for doctors, poor facilities, poor provision of equipment, and the frequent absence of essential drugs.[27][28] A 2023 study by the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights (OCDH), estimated 88% of the population is living in extreme poverty.[29] The traditional diet is of international concern due to micronutrient deficiencies and lack of diversity. As highlighted by the World Food Programme (WFP) of the United Nations, rationed food meets only a fraction of daily nutritional needs for many Cubans, leading to health issues.[30]

Etymology

Historians believe the name Cuba comes from the Taíno language; however, "its exact derivation [is] unknown".[31] The exact meaning of the name is unclear, but it may be translated either as 'where fertile land is abundant' (cubao),[32] or 'great place' (coabana).

History

Pre-Columbian era

Humans first settled Cuba around 6,000 years ago, descending from migrations from northern South America or Central America.[33] The arrival of humans on Cuba is associated with extinctions of the islands native fauna, particularly its endemic sloths.[34] The Arawakan-speaking ancestors of the Taíno people arrived in the Caribbean in a separate migration from South America around 1,700 years ago. Unlike the previous settlers of Cuba, the Taíno extensively produced pottery and engaged in intensive agriculture.[33] The earliest evidence of the Taíno people on Cuba dates to the 9th century AD.[35] Descendants of the first settlers of Cuba persisted on the western part of the island until Columbian contact, where they were recorded as the Guanahatabey people, who lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[36][33]

Spanish colonization and rule (1492–1898)

After first landing on an island then called Guanahani on 12 October 1492,[37] Christopher Columbus landed on Cuba on 27 October 1492, and landing in the northeastern coast on 28 October.[38] Columbus claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain[39] and named it Isla Juana ("John's Island") after John, Prince of Asturias.[40]

In 1511, the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa. Other settlements soon followed, including San Cristobal de la Habana, founded in 1514 (southern coast of the island) and then in 1519 (current place), which later became the capital (1607). The Indigenous Taíno were forced to work under the encomienda system,[41] which resembled the feudal system in medieval Europe.[42] Within a century, the Indigenous people faced high incidence of mortality due to multiple factors, primarily Eurasian infectious diseases, to which they had no natural resistance (immunity), aggravated by the harsh conditions of the repressive colonial subjugation.[43] In 1529, a measles outbreak killed two-thirds of those few Natives who had previously survived smallpox.[44][45]

On 18 May 1539, conquistador Hernando de Soto departed from Havana with some 600 followers into a vast expedition through the American Southeast, in search of gold, treasure, fame and power.[46] On 1 September 1548, Gonzalo Perez de Angulo was appointed governor of Cuba. He arrived in Santiago, Cuba, on 4 November 1549, and immediately declared the liberty of all Natives.[47] He became Cuba's first permanent governor to reside in Havana instead of Santiago, and he built Havana's first church made of masonry.[48][e]

By 1570, most residents of Cuba comprised a mixture of Spanish, African, and Taíno heritages.[50] Cuba developed slowly and, unlike the plantation islands of the Caribbean, had a diversified agriculture. Most importantly, the colony developed as an urbanized society that primarily supported the Spanish colonial empire. By the mid-18th century, there were 50,000 slaves on the island. Estimates suggest that between 1790 and 1820 some 325,000 Africans were imported to Cuba as slaves, which was four times the amount that had arrived between 1760 and 1790.[51]

In 1812, the Aponte Slave Rebellion took place, but it was ultimately suppressed.[52] The population of Cuba in 1817 was 630,980 (of which 291,021 were white, 115,691 were free people of color (mixed-race), and 224,268 black slaves).[53]

In part due to Cuban slaves working primarily in urbanized settings, by the 19th century, the practice of coartacion had developed (or "buying oneself out of slavery", a "uniquely Cuban development"), according to historian Herbert S. Klein.[54] Due to a shortage of white labor, blacks dominated urban industries "to such an extent that when whites in large numbers came to Cuba in the middle of the nineteenth century, they were unable to displace Negro workers."[55] A system of diversified agriculture, with small farms and fewer slaves, served to supply the cities with produce and other goods.[55]

In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal to Spain. Its economy was based on serving the empire. By 1860, Cuba had 213,167 free people of color (39% of its non-white population of 550,000).[55]

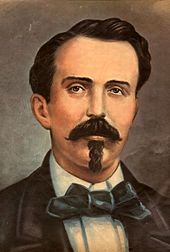

Independence movements

Full independence from Spain was the goal of a rebellion in 1868 led by planter Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. De Céspedes, a sugar planter, freed his slaves to fight with him for an independent Cuba. On 27 December 1868, he issued a decree condemning slavery in theory but accepting it in practice and declaring free any slaves whose masters present them for military service.[56] The 1868 rebellion resulted in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War.

According to one military historian, "The thirty-eight individuals who responded to the call for independence on 9 October 1868 had almost no military experience. They, and other Cubans, ignorant of the martial skills, were soon joined by a small band of political refugees from Santo Domingo. A number of these individuals had fought for Spain in Santo Domingo following its re-annexation (1861–65). When Spain quit Santo Domingo for the second time, some Dominican colonial officers immigrated to Cuba. Most were unable to find service in the Spanish army in Cuba. Some of these former soldiers joined the new Revolutionary army and provided its initial training and leadership."[57] Mercenaries from Canada, Colombia, France, Mexico, and the United States also joined the Cuban Revolutionary Army. Chinese nationals, brought to Cuba as indentured servants, also fought for the cause.[57]

By 1876, the Cuban Revolutionary movement was facing internal strife, largely driven by racial tensions. General Máximo Gómez surrendered his command after officers refused to follow his orders because he was Dominican. At the same time, the campaign against Antonio Maceo, a mulatto leader, grew stronger as white factions sought to undermine his leadership because of his race. These racial divisions contributed to a decline in morale within the Revolutionary Army.[58]

The United States declined to recognize the new Cuban government, although many European and Latin American nations did so.[59] In 1878, the Pact of Zanjón ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. In 1879–80, Cuban patriot Calixto García attempted to start another war known as the Little War but failed to receive enough support.[60] Slavery in Cuba was abolished in 1875 but the process was completed only in 1886.[61][62] An exiled dissident named José Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York City in 1892. The aim of the party was to achieve Cuban independence from Spain.[63] In January 1895, Martí traveled to Monte Cristi and Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez.[63] Martí recorded his political views in the Manifesto of Montecristi.[64] Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Martí was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895.[63] Martí was killed in the Battle of Dos Rios on 19 May 1895.[63] His death immortalized him as Cuba's national hero.[64]

Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army, which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler, the military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called reconcentrados, described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th-century concentration camps.[65] Between 200,000[66] and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the Spanish concentration camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross and United States Senator Redfield Proctor, a former Secretary of War. American and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.[67]

The U.S. battleship USS Maine was sent to protect American interests, but soon after arrival, it exploded in Havana harbor and sank quickly, killing nearly three-quarters of the crew. The cause and responsibility for the sinking of the ship remained unclear after a board of inquiry. Popular opinion in the U.S., fueled by active yellow press, concluded that the Spanish were to blame and demanded action.[68] Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April 1898.[f]

Republic (1902–1959)

First years (1902–1925)

After the Spanish–American War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Spain ceded Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States for the sum of US$20 million[71] and Cuba became a protectorate of the United States. Cuba gained formal independence from the U.S. on 20 May 1902, as the Republic of Cuba.[72] Under Cuba's new constitution, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment, the U.S. leased the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base from Cuba.

Following disputed elections in 1906, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces.[73] The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon as Governor for three years. Cuban historians have characterized Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption.[74] In 1908, self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez was elected president, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912, the Partido Independiente de Color attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province,[75] but was suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

In 1924, Gerardo Machado was elected president.[76] During his administration, tourism increased markedly, and American-owned hotels and restaurants were built to accommodate the influx of tourists.[76] The tourist boom led to increases in gambling and prostitution in Cuba.[76] The Wall Street Crash of 1929 led to a collapse in the price of sugar, political unrest, and repression.[77] Protesting students, known as the Generation of 1930, turned to violence in opposition to the increasingly unpopular Machado.[77] A general strike (in which the Communist Party sided with Machado),[78] uprisings among sugar workers, and an army revolt forced Machado into exile in August 1933. He was replaced by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada.[77]

Revolution of 1933–1940

In September 1933, the Sergeants' Revolt, led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista, overthrew Céspedes.[79] A five-member executive committee (the Pentarchy of 1933) was chosen to head a provisional government.[80] Ramón Grau San Martín was then appointed as provisional president.[80] Grau resigned in 1934, leaving the way clear for Batista, who dominated Cuban politics for the next 25 years, at first through a series of puppet-presidents.[79] The period from 1933 to 1937 was a time of "virtually unremitting social and political warfare".[81] On balance, during the period 1933–1940 Cuba suffered from fragile political structures, reflected in the fact that it saw three different presidents in two years (1935–1936), and in the militaristic and repressive policies of Batista as Head of the Army.

Constitution of 1940

A new constitution was adopted in 1940, which engineered radical progressive ideas, including the right to labor and health care.[82] Batista was elected president in the same year, holding the post until 1944.[83] He is so far the only non-white Cuban to win the nation's highest political office.[84][85][86] His government carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration.[87] Cuban armed forces were not greatly involved in combat during World War II—though president Batista did suggest a joint U.S.-Latin American assault on Francoist Spain to overthrow its authoritarian regime.[88] Cuba lost six merchant ships during the war, and the Cuban Navy was credited with sinking the German submarine U-176.[89]

Batista adhered to the 1940 constitution's strictures preventing his re-election.[90] Ramon Grau San Martin was the winner of the next election, in 1944.[83] Grau further corroded the base of the already teetering legitimacy of the Cuban political system, in particular by undermining the deeply flawed, though not entirely ineffectual, Congress and Supreme Court.[91] Carlos Prío Socarrás, a protégé of Grau, became president in 1948.[83] The two terms of the Auténtico Party brought an influx of investment, which fueled an economic boom, raised living standards for all segments of society, and created a middle class in most urban areas.[92]

Batista regime

After finishing his term in 1944 Batista lived in Florida, returning to Cuba to run for president in 1952. Facing certain electoral defeat, he led a military coup that preempted the election.[93] Back in power, and receiving financial, military, and logistical support from the United States government, Batista suspended the 1940 Constitution and revoked most political liberties, including the right to strike. He then aligned with the wealthiest landowners who owned the largest sugar plantations, and presided over a stagnating economy that widened the gap between rich and poor Cubans.[94] Batista outlawed the Cuban Communist Party in 1952.[95] After the coup, Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios, though about one-third of the population was considered poor and enjoyed relatively little of this consumption.[96] However, in his "History Will Absolve Me" speech, Fidel Castro mentioned that national issues relating to land, industrialization, housing, unemployment, education, and health were contemporary problems.[97]

In 1958, Cuba was a well-advanced country in comparison to other Latin American regions.[98] Cuba was also affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities.[99] Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems.[84][100] Unemployment became a problem as graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs.[84] The middle class, which was comparable to that of the United States[how?], became increasingly dissatisfied with unemployment and political persecution. The labor unions, manipulated by the previous government since 1948 through union "yellowness", supported Batista until the very end.[84][85] Batista stayed in power until he resigned in December 1958 under the pressure of the US Embassy and as the revolutionary forces headed by Fidel Castro were winning militarily (Santa Clara city, a strategic point in the middle of the country, fell into the rebels hands on December 31, in a conflict known as the Battle of Santa Clara).[101][102]

In the 1950s, various organizations, including some advocating armed uprising, competed for public support in bringing about political change.[103] In 1956, Fidel Castro and about 80 supporters landed from the yacht Granma in an attempt to start a rebellion against the Batista government.[103] In 1958, Castro's July 26th Movement emerged as the leading revolutionary group.[103] The U.S. supported Castro by imposing a 1958 arms embargo against Batista's government. Batista evaded the American embargo and acquired weapons from the Dominican Republic.

By late 1958, the rebels had broken out of the Sierra Maestra and launched a general popular insurrection. After Castro's fighters captured Santa Clara, Batista fled with his family to the Dominican Republic on 1 January 1959. Later he went into exile on the Portuguese island of Madeira and finally settled in Estoril, near Lisbon. Fidel Castro's forces entered the capital on 8 January 1959. The liberal Manuel Urrutia Lleó became the provisional president.[104] One of the goals of Castro's revolution was to achieve economic independence, but Cuba instead became heavily dependent on Soviet subsidies, with additional economic aid provided by Eastern European countries through COMECON.[105]

Militant anti-Castro groups, funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Rafael Trujillo, carried out armed attacks and set up guerrilla bases in Cuba's mountainous regions. This led to the unsuccessful Escambray rebellion (1959–65), which lasted longer and involved more soldiers than the Cuban Revolution.[106][107]

Revolutionary government (1959–present)

Consolidation and nationalization (1959–1970)

According to Amnesty International, official death sentences from 1959 to 1987 numbered 237 of which all but 21 were carried out.[108] The vast majority of those executed directly following the 1959 Revolution were policemen, politicians, and informers of the Batista regime accused of crimes such as torture and murder, and their public trials and executions had widespread popular support among the Cuban population.[109]

The United States government initially reacted favorably to the Cuban Revolution, seeing it as part of a movement to bring democracy to Latin America.[111] Castro's legalization of the Communist Party and the hundreds of executions of Batista agents, policemen, and soldiers that followed caused a deterioration in the relationship between the two countries.[111] The promulgation of the Agrarian Reform Law, expropriating thousands of acres of farmland (including from large U.S. landholders), further worsened relations.[111][112] In response, between 1960 and 1964 the U.S. imposed a range of sanctions, eventually including a total ban on trade between the countries and a freeze on all Cuban-owned assets in the U.S.[113] In February 1960, Castro signed a commercial agreement with Soviet Vice-Premier Anastas Mikoyan.[111]

In March 1960, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave his approval to a CIA plan to arm and train a group of Cuban refugees to overthrow the Castro government. The CIA provided B-26 light bombers and ships to the rebels for the invasion. On 15 April 1961 at dawn, Brigade 2506 flew from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, and carried out preemptive airstrikes on Cuban military airfields at San Antonio de Los Baños, Ciudad Libertad, Pinar del Río, and Santiago de Cuba, destroying five aircraft and damaging an indeterminable number.[114] The invasion (known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion) took place on 17 April 1961, during the term of President John F. Kennedy.[112] About 1,400 Cuban exiles disembarked at the Bay of Pigs. Cuban troops and local militias defeated the invasion by 19 April, killing over 100 invaders and taking the remainder prisoner.[112] Five rebel B-26s were shot down by the Cuban air force, and one was downed by anti-aircraft fire.[115] In January 1962, Cuba was suspended from the Organization of American States (OAS), and later the same year the OAS started to impose sanctions against Cuba of similar nature to the U.S. sanctions.[116] The failed amphibious assault on Cuba contributed to the Soviet decision to deploy missiles there,[117] and the ensuing Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 almost sparked World War III.[118][119] In 1962, American generals proposed Operation Northwoods which would entail committing terrorist attacks in American cities and against refugees and falsely blaming the attacks on the Cuban government, manufacturing a reason for the United States to invade Cuba. This plan was rejected by President Kennedy.[120] By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged communist system modeled on the USSR.[121]

Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo founded the anti-Castro group Alpha 66 in the early 1960s, which used small craft to attack Cuban and Soviet merchant ships, killing or wounding crew members. In 1964, Menoyo set up a guerrilla training camp in the Dominican Republic, and after entering Cuba in 1965, he was captured; however, Alpha 66 continued its raids under new leadership.[122] By the mid-1960s, Soviet aid had strengthened the Cuban air force and navy, making raids against the island by Cuban dissidents costly without significant U.S. support.[123]

In 1963, Cuba sent 686 troops together with 22 tanks and other military equipment to support Algeria in the Sand War against Morocco.[124] The Cuban forces remained in Algeria for over a year, providing training to the Algerian army.[125] Che Guevara, authorized by Fidel Castro, engaged in guerrilla activities in Africa and was killed in 1967 while attempting to start a revolution in Bolivia.[50] By the middle of 1965, Cuba had begun supplying arms to the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). In 1966, Cuban aid also reached the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde. Furthermore, by the late 1960s, Cuban instructors were providing military training to members of the Mozambique Liberation Front.[125] Cuban troops prevented the 1966 Republic of the Congo coup attempt. The coup collapsed when the Congolese army refused to engage in combat against the Cubans.[125] In February 1967, Cuban advisors began operating with guerrillas in the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence, and in November 1969, the Portuguese captured Cuban Captain Pedro Rodriguez Peralta.[125]

Starting in 1968 a campaign titled the "revolutionary offensive" was initiated to nationalize all remaining private small businesses, which at the time totaled to be about 58,000 small enterprises.[126] The campaign would spur industrialization in Cuba and focus the economy on sugar production, specifically to a deadline for an annual sugar harvest of 10 million tons by 1970. The economic focus on sugar production involved international volunteers and the mobilization of workers from all sectors of the Cuban economy.[127] Economic mobilization also coincided with greater militarization of Cuban political structures and society in general.[128] The ten million ton harvest goal was not reached.[129]: 37–38 The Cuban economy fell into decline after large sectors of the economy were neglected when large amounts of urban labor mobilized to the countryside.[129]: 38

The standard of living in the 1970s was "extremely spartan" and discontent was rife.[130] Fidel Castro admitted the failures of economic policies in a 1970 speech.[130] In 1975, the OAS lifted its sanctions against Cuba, with the approval of 16 member states, including the United States. The U.S., however, maintained its own sanctions.[116]

Foreign interventions (1971–1991)

During the Cold War, Cuba received $33 billion in Soviet aid,[105] and Cuban forces were deployed to all corners of Africa, either as military advisors or as combatants.[131] Soviet pilots and technicians assumed defense duties in Cuba, freeing up Cuban personnel to be deployed in Africa.[125] In 1979, the U.S. objected to the presence of Soviet combat troops on the island.[50]

In November 1975, Cuba deployed more than 65,000 troops and 400 Soviet-made tanks in Angola in one of the fastest military mobilizations in history.[132] South Africa developed nuclear weapons due to the threat to its security posed by the presence of large numbers of Cuban troops in Angola.[133] In 1975-76 and again in 1988 at the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, the Cubans alongside their MPLA allies fought UNITA rebels and apartheid South African forces. In December 1977, Cuba sent its combat troops from Angola, the People's Republic of the Congo, and the Caribbean to Ethiopia,[125] assisted by mechanized Soviet battalions, to help defeat a Somali invasion. On 24 January 1978, Ethiopian and Cuban troops counterattacked, inflicting 3,000 casualties on the Somali forces.[125] In February, Cuban troops launched a major offensive and forced the Somali army back into its own territory.[125] Cuban forces remained in Ethiopia until September 1989.[125]

Despite Cuba's small size and the long distance separating it from the Middle East, Castro's Cuba played an active role in the region during the Cold War. In 1972, a major Cuban military mission consisting of tank, air, and artillery specialists was dispatched to South Yemen. Cuban military advisors were sent to Iraq in the mid-1970s but their mission was canceled after Iraq invaded Iran in 1980.[125] The Cubans were also involved in the Syrian-Israeli conflict (November 1973–May 1974) that followed the Yom Kippur War (October 1973).[134] Israeli sources reported the presence of a Cuban tank brigade in the Golan Heights, which was supported by two brigades.[135] The Israelis and the Cuban-Syrian tank forces engaged in battle on the Golan front.[136]: 37–38

After the U.S. was defeated in the Vietnam War, Castro began supporting Marxist insurgencies in Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Colombia by supplying weapons, munitions, and training.[137] Following the 1983 coup that resulted in the execution of Grenadian Prime Minister Maurice Bishop and establishment of the military government led by Hudson Austin, U.S. forces invaded Grenada in 1983, overthrowing the pro-Castro government. In a few days of fighting, 6,000 American combat troops defeated 784 Cubans (636 construction workers with military training, 43 military advisors, and 18 diplomats).[138]

Cuba gradually withdrew its troops from Angola in 1989–91.[125] An important psychological and political aspect of the Cuban military involvement in Africa was the significant presence of black or mixed-race soldiers among the Cuban forces. According to one source, more than 300,000 Cuban military personnel and civilian experts were deployed in Africa. The source also states that out of the 50,000 Cubans sent to Angola, half contracted AIDS and that 10,000 Cubans died as a consequence of their military actions in Africa.[125]

Political readjustments (1991–present)

Soviet troops began to withdraw from Cuba in September 1991,[50] and Castro's rule was severely tested in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse in December 1991 (known in Cuba as the Special Period). The country faced a severe economic downturn following the withdrawal of Soviet subsidies worth $4 billion to $6 billion annually, resulting in effects such as food and fuel shortages.[139][140] The government did not accept American donations of food, medicines and cash until 1993.[139] On 5 August 1994, state security dispersed protesters in a spontaneous protest in Havana. From the start of the crisis until 1995, Cuba saw its gross domestic product (GDP) shrink by 35%. It took another five years for its GDP to reach pre-crisis levels.[141]

Cuba has since found a new source of aid and support in the People's Republic of China. In addition, Hugo Chávez, then president of Venezuela, and Evo Morales, former president of Bolivia, became allies and both countries are major oil and gas exporters. In 2003, the government arrested and imprisoned a large number of civil activists, a period known as the "Black Spring".[142][143]

In February 2008, Fidel Castro resigned as President of the State Council due to the serious gastrointestinal illness which he had suffered since July 2006.[144] On 24 February, the National Assembly elected his brother Raúl Castro the new president.[145] In his inauguration speech, Raúl promised that some of the restrictions on freedom in Cuba would be removed.[146] In March 2009, Raúl Castro removed some of his brother's appointees.[147]

On 3 June 2009, the Organization of American States adopted a resolution to end the 47-year ban on Cuban membership of the group.[148] The resolution stated, however, that full membership would be delayed until Cuba was "in conformity with the practices, purposes, and principles of the OAS".[116] Fidel Castro wrote that Cuba would not rejoin the OAS, which, he said, was a "U.S. Trojan horse" and "complicit" in actions taken by the U.S. against Cuba and other Latin American nations.[149]

Effective 14 January 2013, Cuba ended the requirement established in 1961, that any citizens who wish to travel abroad were required to obtain an expensive government permit and a letter of invitation.[150][151][152] In 1961 the Cuban government had imposed broad restrictions on travel to prevent the mass emigration of people after the 1959 revolution;[153] it approved exit visas only on rare occasions.[154] Requirements were simplified: Cubans need only a passport and a national ID card to leave; and they are allowed to take their young children with them for the first time.[155] However, a passport costs on average five months' salary. Observers expect that Cubans with paying relatives abroad are most likely to be able to take advantage of the new policy.[156] In the first year of the program, over 180,000 left Cuba and returned. As of December 2014[update], talks with Cuban officials and American officials, including President Barack Obama, resulted in the release of Alan Gross, fifty-two political prisoners, and an unnamed non-citizen agent of the United States in return for the release of three Cuban agents currently imprisoned in the United States. Additionally, while the embargo between the United States and Cuba was not immediately lifted, it was relaxed to allow import, export, and certain limited commerce.[157]

Raúl Castro stepped down from the presidency on 19 April 2018 and Miguel Díaz-Canel was elected president by the National Assembly following parliamentary elections. Raúl Castro remained the First Secretary of the Communist Party and retained broad authority, including oversight over the president.[158]

Cuba approved a new constitution in 2019. The optional vote attracted 84.4% of eligible voters. 90% of those who voted approved of the new constitution and 9% opposed it. The new constitution states that the Communist Party is the only legitimate political party, describes access to health and education as fundamental rights, imposes presidential term limits, enshrines the right to legal representation upon arrest, recognizes private property, and strengthens the rights of multinationals investing with the state.[159] Any form of discrimination harmful to human dignity is banned under the new constitution.[160]

Raúl Castro announced at the Eighth Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba, which began on 16 April 2021, that he was retiring as secretary of the Communist Party.[161] His successor, Miguel Díaz-Canel, was voted in on 19 April.[162]

In July 2021, there were several large protests against the government under the banner of Patria y Vida. Cuban exiles also conducted protests overseas.[163][164][165] The song associated with the movement received international acclaim including a Latin Grammy Award.[166]

On 25 September 2022, Cuba approved a referendum which amended the Family Code to legalise same-sex marriage and allow surrogate pregnancy and same-sex adoption. Gender reassignment surgery and transgender hormone therapy are provided free of charge under Cuba's national healthcare system. The proposed changes were supported by the government and opposed by conservatives and parts of the opposition. Official policies of the Cuban government from 1959 until the 1990s were hostile towards homosexuality, with the LGBT community marginalized on the basis of heteronormativity, traditional gender roles, and strict criteria for moralism.[160][167]

Geography

Cuba is an archipelago of 4,195 islands, cays and islets located in the northern Caribbean Sea at the confluence with the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. It lies between latitudes 19° and 24°N, and longitudes 74° and 85°W. Florida (Key West, Florida) is about 150 km (93 miles) across the Straits of Florida to the north and northwest, and The Bahamas (Cay Lobos) 22.5 km (14 mi) to the north. Mexico lies 210 km (130.5 mi) west across the Yucatán Channel (to the closest tip of Cabo Catoche in the State of Quintana Roo).

Haiti is 77 km (47.8 mi) east and Jamaica 140 km (87 mi) south. Cuba is the principal island, surrounded by four smaller groups of islands: the Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast, the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast, the Jardines de la Reina on the south-central coast and the Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast.

The main island, named Cuba, is 1,250 km (780 mi) long, constituting most of the nation's land area (104,338 km2 or 40,285 sq mi) and is the largest island in the Caribbean and 17th-largest island in the world by land area. The main island consists mostly of flat to rolling plains apart from the Sierra Maestra mountains in the southeast, whose highest point is Pico Turquino (1,974 m or 6,476 ft).

The second-largest island is Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in the Canarreos archipelago, with an area of 2,204 km2 (851 sq mi). Cuba has an official area of 109,884 km2 (42,426 sq mi). Its area is 110,860 km2 (42,803 sq mi) including coastal and territorial waters.

Climate

With the entire island south of the Tropic of Cancer, the local climate is tropical, moderated by northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. The temperature is also shaped by the Caribbean current, which brings in warm water from the equator. This makes the climate of Cuba warmer than that of Hong Kong, which is at around the same latitude as Cuba but has a subtropical rather than a tropical climate. In general (with local variations), there is a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. The average temperature is 21 °C (70 °F) in January and 27 °C (81 °F) in July. The warm temperatures of the Caribbean Sea and the fact that Cuba sits across the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico combine to make the country prone to frequent hurricanes. These are most common in September and October.

Hurricane Irma hit the island on 8 September 2017, with winds of 260 km/h (72 m/s),[168] at the Camagüey Archipelago; the storm reached Ciego de Avila province around midnight and continued to pound Cuba the next day.[169] The worst damage was in the keys north of the main island. Hospitals, warehouses and factories were damaged; much of the north coast was without electricity. By that time, nearly a million people, including tourists, had been evacuated.[170] The Varadero resort area also reported widespread damage; the government believed that repairs could be completed before the start of the main tourist season.[171] Subsequent reports indicated that ten people had been killed during the storm, including seven in Havana, most during building collapses. Sections of the capital had been flooded.[171]

Biodiversity

Cuba signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 12 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 8 March 1994.[172] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, with one revision, that the convention received on 24 January 2008.[173]

The country's fourth national report to the CBD contains a detailed breakdown of the numbers of species of each kingdom of life recorded from Cuba, the main groups being: animals (17,801 species), bacteria (270), chromista (707), fungi, including lichen-forming species (5,844), plants (9,107) and protozoa (1,440).[174] The native bee hummingbird or zunzuncito is the world's smallest known bird, with a length of 55 mm (2+1⁄8 in). The Cuban trogon or tocororo is the national bird of Cuba and an endemic species. Other endemic species are the Cuban crocodile, Cuban hutia, Cuban solenodon, Cuban gar, Cuban boa, and Polymita picta. Hedychium coronarium, named mariposa in Cuba, is the national flower.[175]

Cuba is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Cuban moist forests, Cuban dry forests, Cuban pine forests, Cuban wetlands, Cuban cactus scrub, and Greater Antilles mangroves.[176] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.4/10, ranking it 102nd globally out of 172 countries.[177]

According to a 2012 study, Cuba is the only country in the world to meet the conditions of sustainable development put forth by the WWF.[178]

Government and politics

The Republic of Cuba is one of the few socialist countries following the Marxist–Leninist ideology. The Constitution of 1976, which defined Cuba as a socialist republic, was replaced by the Constitution of 1992, which is "guided by the ideas of José Martí and the political and social ideas of Marx, Engels and Lenin."[179] The constitution describes the Communist Party of Cuba as the "leading force of society and of the state".[179] The political system in Cuba reflects the Marxist–Leninist concept of democratic centralism.[180]: 38

The First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba is the most senior position in the one-party state.[181] The First Secretary leads the Politburo and the Secretariat, making the office holder the most powerful person in Cuban government.[182] Members of both councils are elected by the National Assembly of People's Power.[179] The President of Cuba, who is also elected by the Assembly, serves for five years and since the ratification of the 2019 Constitution, there is a limit of two consecutive five-year terms.[179]

The People's Supreme Court serves as Cuba's highest judicial branch of government. It is also the court of last resort for all appeals against the decisions of provincial courts.

Cuba's national legislature, the National Assembly of People's Power (Asamblea Nacional de Poder Popular), is the supreme organ of power; 474 members serve five-year terms.[179] The assembly meets twice a year; between sessions legislative power is held by the 31 member Council of Ministers. Candidates for the Assembly are approved by public referendum. All Cuban citizens over 16 who have not been convicted of a criminal offense can vote.[183] Article 131 of the Constitution states that voting shall be "through free, equal and secret vote".[179] Article 136 states: "In order for deputies or delegates to be considered elected they must get more than half the number of valid votes cast in the electoral districts".[179]

There are elections in Cuba, but they are not considered democratic.[184][185] In elections for the National Assembly of People's Power there is only one candidate for each seat, and candidates are nominated by committees that are firmly controlled by the Communist Party.[186][187] Most legislative districts elect multiple representatives to the Assembly. Voters can select individual candidates on their ballot, select every candidate, or leave every question blank, with no option to vote against candidates.[188][189]

No political party is permitted to nominate candidates or campaign on the island, including the Communist Party.[190] The Communist Party of Cuba has held six party congress meetings since 1975. In 2011, the party stated that there were 800,000 members, and representatives generally constitute at least half of the Councils of state and the National Assembly. The remaining positions are filled by candidates nominally without party affiliation. Other political parties campaign and raise finances internationally, while activity within Cuba by opposition groups is minimal.

Cuba is considered an authoritarian regime according to The Economist's Democracy Index[191] and Freedom in the World reports.[192] More specifically, Cuba is considered a military dictatorship in the Democracy-Dictatorship Index, and has been described as "a militarized society"[193] with the armed forces having long been the most powerful institution in the country.[194]

In February 2013, President of the State Council Raúl Castro announced he would resign in 2018, ending his five-year term, and that he hopes to implement permanent term limits for future Cuban presidents, including age limits.[195]

After Fidel Castro died on 25 November 2016, the Cuban government declared a nine-day mourning period. During the mourning period, Cuban citizens were prohibited from playing loud music, partying, and drinking alcohol.[196]

Miguel Díaz-Canel was elected president on 18 April 2018 after the resignation of Raúl Castro. On 19 April 2021, Díaz-Canel became First Secretary of the Communist Party. He is the first non-Castro to be in such top position since the Cuban revolution of 1959.[197]

Administrative divisions

The country is subdivided into 15 provinces and one special municipality (Isla de la Juventud). These were formerly part of six larger historical provinces: Pinar del Río, Habana, Matanzas, Las Villas, Camagüey and Oriente. The present subdivisions closely resemble those of the Spanish military provinces during the Cuban Wars of Independence, when the most troublesome areas were subdivided. The provinces are divided into municipalities.

Foreign relations

Cuba has conducted a foreign policy that is uncharacteristic of such a minor, developing country.[198][199] Under Castro, Cuba was heavily involved in wars in Africa, Central America and Asia. Cuba supported Algeria in 1961–1965[200] and sent tens of thousands of troops to Angola during the Angolan Civil War.[201] Other countries that featured Cuban involvement include Ethiopia,[202][203] Guinea,[204] Guinea-Bissau,[205] Mozambique,[206] and Yemen.[207] Lesser known actions include the 1959 missions to the Dominican Republic.[208] The expedition failed, but a prominent monument to its members was erected in their memory in Santo Domingo by the Dominican government, and they feature prominently at the country's Memorial Museum of the Resistance.[209]

In 2008, the European Union (EU) and Cuba agreed to resume full relations and cooperation activities.[210] Cuba is a founding member of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas.[211] At the end of 2012, tens of thousands of Cuban medical personnel worked abroad,[212] with as many as 30,000 doctors in Venezuela alone via the two countries' oil-for-doctors programme.[213]

In 1996, the United States, then under President Bill Clinton, brought in the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, better known as the Helms–Burton Act.[214][g] In 2009, United States President Barack Obama stated on 17 April, in Trinidad and Tobago that "the United States seeks a new beginning with Cuba",[216] and reversed the Bush Administration's prohibition on travel and remittances by Cuban-Americans from the United States to Cuba.[217] Five years later, an agreement between the United States and Cuba, popularly called the "Cuban thaw", brokered in part by Canada and Pope Francis, began the process of restoring international relations between the two countries. They agreed to release political prisoners and the United States began the process of creating an embassy in Havana.[218][219][220][221][222] This was realized on 30 June 2015, when Cuba and the U.S. reached a deal to reopen embassies in their respective capitals on 20 July 2015[223] and reestablish diplomatic relations.[224] Earlier in the same year, the White House announced that President Obama would remove Cuba from the American government's list of nations that sponsor terrorism,[225][226] which Cuba reportedly welcomed as "fair".[227] On 17 September 2017, the United States considered closing its Cuban embassy following mysterious medical symptoms experienced by its staff.[228] In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing international isolation of Russia, Cuba emerged as one of the few countries that maintained friendly relations with the Russian Federation.[229][230] Cuban president Miguel Diaz-Canel visited Vladimir Putin in Moscow in November 2022, where the two leaders opened a monument of Fidel Castro, as well as speaking out against U.S. sanctions against Russia and Cuba.[231]

Embargo by the United States (1960–present)

Since 1960, the U.S. embargo on Cuba stands as one of the longest-running trade and economic measures in bilateral relations history, having endured for almost six decades. This action was initiated in response to a wave of nationalizations that impacted American properties valued at over US$1 billion, the then U.S.[232] President, Dwight Eisenhower, instated an embargo that prohibited all exports to Cuba, with the exception of medicines and certain foods.[232] This measure was intensified in 1962 under the administration of John F. Kennedy, extending the restrictions to Cuban imports, based on the Foreign Assistance Act approved by Congress in 1961.[232] During the Missile Crisis in 1962, the United States even imposed a naval blockade on Cuba, but this was lifted following the resolution of the crisis. The embargo, however, remained in place and has been modified on several occasions over the years.[232]

The Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 states that sanctions will continue "so long as it continues to refuse to move toward democratization and greater respect for human rights".[233][non-primary source needed] American diplomat Lester D. Mallory wrote an internal memo on April 6, 1960, arguing in favor of an embargo: "The only foreseeable means of alienating internal support is through disenchantment and disaffection based on economic dissatisfaction and hardship. [...] to decrease monetary and real wages, to bring about hunger, desperation and overthrow of government."[234][235] The UN General Assembly has passed a resolution every year since 1992 condemning the embargo and stating that it violates the Charter of the United Nations and international law.[236] Cuba considers the embargo a human rights violation.[237]

The impact and effectiveness of the embargo have been subjects of intense debate. While some argue it has been "extraordinarily porous" and isn't the primary cause of Cuba's economic hardships, others see it as a pressure mechanism aimed at driving change in the Cuban government.[232] According to Arturo Lopez Levy, a professor of international relations, it would be more appropriate to refer to the measure as a "blockade" or "siege", as it goes beyond mere trade restrictions.[232] Other critics of the Cuban government argue that the embargo has been used by the government as an excuse to justify its own economic and political shortcomings.[232]

On 17 December 2014, United States President Barack Obama announced the re-establishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba, pushing for Congress to put an end to the embargo,[238] as well as the United States-run Guantanamo Bay detention camp. These diplomatic improvements were later reversed by the Trump Administration, which enacted new rules and re-enforced the business and travel restrictions which were loosened by the Obama Administration.[239] These sanctions were inherited and strengthened by the Biden Administration.[240]

Despite the embargo, Cuba has maintained trade relations with other countries.[232] According to 2019 data, China stands as Cuba's main trading partner, followed by countries such as Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, and Cyprus. Cuba's main exports include tobacco, sugar, and alcoholic beverages, while it primarily imports chicken meat, wheat, corn, and condensed milk.[232]

Military

As of 2018[update], Cuba spent about US$91.8 million on its armed forces or 2.9% of its GDP.[241] In 1985, Cuba devoted more than 10% of its GDP to military expenditures.[242] During the Cold War, Cuba built up one of the largest armed forces in Latin America, second only to that of Brazil.[243]

From 1975 until the late 1980s, Soviet military assistance enabled Cuba to upgrade its military capabilities. After the loss of Soviet subsidies, Cuba scaled down the numbers of military personnel, from 235,000 in 1994 to about 49,000 in 2021.[244][245]

In 2017, Cuba signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[246]

Cuba is the 98th most peaceful country in the world, according to the 2024 Global Peace Index.[247]

Law enforcement

All law enforcement agencies are maintained under Cuba's Ministry of the Interior, which is supervised by the Revolutionary Armed Forces. In Cuba, citizens can receive police assistance by dialing "106" on their telephones.[248] The police force, which is referred to as "Policía Nacional Revolucionaria" or PNR is then expected to provide help. The Cuban government also has an agency called the Intelligence Directorate that conducts intelligence operations and maintains close ties with the Russian Federal Security Service.[249] The US Justice Department considers Cuba a significant counterintelligence threat.[250]

Civilians are also involved in law enforcement, in a limited capacity. The Committees for the Defense of the Revolution are an official neighborhood watch organization, made up of dedicated citizens who monitor their neighbors.[251] Membership is not selective, but leading members are approved by the Cuban Communist Party.[252]

Human rights

In 2003, the European Union (EU) accused the Cuban government of "continuing flagrant violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms".[253] As of 2009,[update] it has continued to call regularly for social and economic reform in Cuba, along with the unconditional release of all political prisoners.[254]

Cuba was ranked 19th by the number of imprisoned journalists of any nation in 2021[update] according to various sources, including the Committee to Protect Journalists and Human Rights Watch.[255][256] Cuba ranks 171st out of 180 on the 2020[update] World Press Freedom Index.[257]

In July 2010, the unofficial Cuban Human Rights Commission said there were 167 political prisoners in Cuba, a fall from 201 at the start of the year. The head of the commission stated that long prison sentences were being replaced by harassment and intimidation.[258]

Economy

The Cuban state asserts its adherence to socialist principles in organizing its largely state-controlled planned economy. Most of the means of production are owned and run by the government and most of the labor force is employed by the state. Recent years have seen a trend toward more private sector employment. By 2006, public sector employment was 78% and private sector 22%, compared to 91.8% to 8.2% in 1981.[259] Government spending is 78.1% of GDP.[260] Since the early 2010s, following the initial market reforms, it has become popular to describe the economy as being, or moving toward, market socialism.[261][262][263] Any firm that hires a Cuban must pay the Cuban government, which in turn pays the employee in Cuban pesos.[264] The average monthly wage as of July 2013[update] was 466 Cuban pesos—about US$19.[265] However, after a reform in January 2021, the minimum wage is about 2100 CUP (US$18) and the median wage is about 4000 CUP (US$33).[citation needed]

Cuba had Cuban pesos (CUP) set at par with the US dollar before 1959.[265] Every Cuban household has a ration book (known as libreta) entitling it to a monthly supply of food and other staples, which are provided at nominal cost.[266]

According to the Havana Consulting Group, in 2014, remittances to Cuba amounted to US$3,129 million, the seventh highest in Latin America.[267] In 2019, remittances had grown to US$6,616 million, but dropped down to US$1,967 million in 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[268] The pandemic has also devastated Cuba's tourist industry, which along with a tightening of U.S. sanctions, has led to large increase in emigration among younger working-age Cubans. It has been described as a crisis that is "threatening the stability" of Cuba, which "already has one of the hemisphere’s oldest populations".[269] According to a controversial 2023 report by the Cuban Observatory of Human Rights (OCDH), 88% of Cuban citizens live in extreme poverty. The report stated that Cubans were concerned about food security and the difficulty in acquiring basic goods.[270]

According to the World Bank, Cuba's GDP per capita was $9,500 as of 2020.[271] But according to the CIA World Factbook, it was $12,300 as of 2016.[272] The United Nations Development Programme gave Cuba a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.764 in 2021.[273] The same United Nations agency estimated the country's Multidimensional Poverty Index of 0.003 in 2023.[274]

In 2005, Cuba had exports of US$2.4 billion, ranking 114 of 226 world countries, and imports of US$6.9 billion, ranking 87 of 226 countries.[275] Its major export partners are Canada 17.7%, China 16.9%, Venezuela 12.5%, Netherlands 9%, and Spain 5.9% (2012).[276] Cuba's major exports are sugar, nickel, tobacco, fish, medical products, citrus fruits, and coffee;[276] imports include food, fuel, clothing, and machinery. Cuba presently holds debt in an amount estimated at $13 billion,[277] approximately 38% of GDP.[278]

According to The Heritage Foundation, Cuba is dependent on credit accounts that rotate from country to country.[279] Cuba's prior 35% supply of the world's export market for sugar has declined to 10% due to a variety of factors, including a global sugar commodity price drop that made Cuba less competitive on world markets.[280] It was announced in 2008 that wage caps would be abandoned to improve the nation's productivity.[281]

Cuba's leadership has called for reforms in the country's agricultural system. In 2008, Raúl Castro began enacting agrarian reforms to boost food production, as at that time 80% of food was imported. The reforms aim to expand land use and increase efficiency.[282] Venezuela supplies Cuba with an estimated 110,000 barrels (17,000 m3) of oil per day in exchange for money and the services of some 44,000 Cubans, most of them medical personnel, in Venezuela.[283][284]

In 2010[update], Cubans were allowed to build their own houses. According to Raúl Castro, they could now improve their houses, but the government would not endorse these new houses or improvements.[285] There is virtually no homelessness in Cuba,[286][287] and 85% of Cubans own their homes[288] and pay no property taxes or mortgage interest. Mortgage payments may not exceed 10% of a household's combined income.[citation needed].

On 2 August 2011, The New York Times reported that Cuba reaffirmed its intent to legalize "buying and selling" of private property before the year's end. According to experts, the private sale of property could "transform Cuba more than any of the economic reforms announced by President Raúl Castro's government".[289] It would cut more than one million state jobs, including party bureaucrats who resist the changes.[290] The reforms created what some call "New Cuban Economy".[291][292] In October 2013, Raúl said he intended to merge the two currencies, but as of August 2016[update], the dual currency system remains in force.

In 2016, the Miami Herald wrote, "... about 27 percent of Cubans earn under $50 per month; 34 percent earn the equivalent of $50 to $100 per month; and 20 percent earn $101 to $200. Twelve percent reported earning $201 to $500 a month; and almost 4 percent said their monthly earnings topped $500, including 1.5 percent who said they earned more than $1,000."[293]

In May 2019, Cuba imposed rationing of staples such as chicken, eggs, rice, beans, soap and other basic goods. (Some two-thirds of food in the country is imported.) A spokesperson blamed the increased U.S. trade embargo although economists believe that an equally important problem is the massive decline of aid from Venezuela and the failure of Cuba's state-run oil company which had subsidized fuel costs.[294]

In June 2019, the government announced an increase in public sector wages of about 300%, specifically for teachers and health personnel.[295] In October, the government allowed stores to purchase house equipment and similar items, using international currency, and send it to Cuba by emigration. The leaders of the government recognized that the new measures were unpopular but necessary to contain the capital flight to other countries as Panamá where Cuban citizens traveled and imported items to resell on the island. Other measures included allowing private companies to export and import, through state companies, resources to produce products and services in Cuba.

On January 1, 2021, Cuba's dual currency system was formally ended, and the convertible Cuban peso (CUC) was phased out, leaving the Cuban peso (CUP) as the country's sole currency unit. Cuban citizens had until June 2021 to exchange their CUCs. However, this devalued the Cuban peso and caused economic problems for people who had been previously paid in CUCs, particularly workers in the tourism industry.[296][297][298] Also, in February, the government dictated new measures to the private sector, with prohibitions for only 124 activities,[299] in areas like national security, health and educational services.[300] The wages were increased again, between 4 and 9 times, for all the sectors. Also, new facilities were allowed to the state companies, with much more autonomy.[297]

The first problem with the new reform, in terms of public opinion, were electricity prices, but that was amended quickly. Other measures corrected were in the prices for private farmers.[citation needed] In July 2020, Cuba opened new stores accepting only foreign currency while simultaneously eliminating a special tax on the U.S. dollar[301] to combat an economic crisis arising initially due to economic sanctions imposed by the Trump administration,[302] then later worsened by a lack of tourism during the coronavirus pandemic. These economic sanctions have since been sustained by the Biden administration.[303]

Resources

Cuba's natural resources include sugar, tobacco, fish, citrus fruits, coffee, beans, rice, potatoes, and livestock. Cuba's most important mineral resource is nickel, with 21% of total exports in 2011.[304] The output of Cuba's nickel mines that year was 71,000 tons, approaching 4% of world production.[305] As of 2013[update] its reserves were estimated at 5.5 million tons, over 7% of the world total.[305] Sherritt International of Canada operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa. Cuba is also a major producer of refined cobalt, a by-product of nickel mining.[306]

Oil exploration in 2005 by the US Geological Survey revealed that the North Cuba Basin could produce about 4.6 billion barrels (730,000,000 m3) to 9.3 billion barrels (1.48×109 m3) of oil. In 2006, Cuba started to test-drill these locations for possible exploitation.[307]

Tourism

Tourism was initially restricted to enclave resorts where tourists would be segregated from Cuban society, referred to as "enclave tourism" and "tourism apartheid".[308] Contact between foreign visitors and ordinary Cubans were de facto illegal between 1992 and 1997.[309] The rapid growth of tourism during the Special Period had widespread social and economic repercussions in Cuba, and led to speculation about the emergence of a two-tier economy.[310]

1.9 million tourists visited Cuba in 2003, predominantly from Canada and the European Union, generating revenue of US$2.1 billion.[311] Cuba recorded 2,688,000 international tourists in 2011, the third-highest figure in the Caribbean (behind the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico).[312] American tourism was incredibly limited due to the Cuban Missile Crisis until 2016, when most restrictions were limited but some remained in place.[313]

The medical tourism sector caters to thousands of European, Latin American, Canadian, and American consumers every year.[citation needed]

A study in 2018 indicated that Cuba has a potential for mountaineering activity, and that mountaineering could be a key contributor to tourism, along with other activities, e.g. biking, diving, caving. Promoting these resources could contribute to regional development, prosperity, and well-being.[314]

The Cuban Justice minister downplays allegations of widespread sex tourism.[315] According to a Government of Canada travel advice website, "Cuba is actively working to prevent child sex tourism, and a number of tourists, including Canadians, have been convicted of offenses related to the corruption of minors aged 16 and under. Prison sentences range from 7 to 25 years."[316]

Some tourist facilities were extensively damaged on 8 September 2017 when Hurricane Irma hit the island. The storm made landfall in the Camagüey Archipelago; the worst damage was in the keys north of the main island, however, and not in the most significant tourist areas.[170]

Transport

Demographics

According to the official census of 2010, Cuba's population was 11,241,161, comprising 5,628,996 men and 5,612,165 women.[317] Its birth rate (9.88 births per thousand population in 2006)[318] is one of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere. Although the country's population has grown by about four million people since 1961, the rate of growth slowed during that period, and the population began to decline in 2006, due to the country's low fertility rate (1.43 children per woman) coupled with emigration.[319]

Largest cities

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Havana  Santiago de Cuba |

1 | Havana | Havana | 2,131,480 |  Camagüey  Holguín | ||||

| 2 | Santiago de Cuba | Santiago de Cuba | 433,581 | ||||||

| 3 | Camagüey | Camagüey | 308,902 | ||||||

| 4 | Holguín | Holguín | 297,433 | ||||||

| 5 | Santa Clara | Villa Clara | 216,854 | ||||||

| 6 | Guantánamo | Guantánamo | 216,003 | ||||||

| 7 | Victoria de Las Tunas | Las Tunas | 173,552 | ||||||

| 8 | Bayamo | Granma | 159,966 | ||||||

| 9 | Cienfuegos | Cienfuegos | 151,838 | ||||||

| 10 | Pinar del Río | Pinar del Río | 145,193 | ||||||

Ethnoracial groups

Cuba's population is multiethnic, reflecting its complex colonial origins. Intermarriage between diverse groups is widespread, and consequently there is some discrepancy in reports of the country's racial composition: whereas the Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies at the University of Miami determined that 62% of Cubans are black using the one drop rule,[322] the 2002 Cuban census found that a similar proportion of the population, 65.05%, was white.

In fact, the Minority Rights Group International determined that "An objective assessment of the situation of Afro-Cubans remains problematic due to scant records and a paucity of systematic studies both pre- and post-revolution. Estimates of the percentage of people of African descent in the Cuban population vary enormously, ranging from 34% to 62%".[323]

A 2014 study found that, based on ancestry informative markers (AIM), autosomal genetic ancestry in Cuba is 72% European, 20% African, and 8% Indigenous.[324]

Asians make up about 1% of the population, and are largely of Chinese ancestry, followed by Japanese and Filipino.[325][326] Many are descendants of farm laborers brought to the island by Spanish and American contractors during the 19th and early 20th century.[327] The current recorded number of Cubans with Chinese ancestry is 114,240.[328]

Afro-Cubans are descended primarily from the Yoruba people, Bantu people from the Congo basin, Kalabari tribe and Arará from the Dahomey, as well as several thousand North African refugees, most notably the Sahrawi Arabs of Western Sahara.[329]

Migration

Immigration

Immigration and emigration have played a prominent part in Cuba's demographic profile. Between the 18th and early 20th century, large waves of Canarian, Catalan, Andalusian, Galician, and other Spanish people immigrated to Cuba. Between 1899 and 1930 alone, close to a million Spaniards entered Cuba, although many eventually returned to Spain.[330] Other prominent immigrant groups included French,[331] Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Dutch, Greek, British, and Irish, as well as small number of descendants of U.S. citizens who arrived in Cuba in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As of 2015, the foreign-born population in Cuba was 13,336 inhabitants per the World Bank data.[332]

Emigration

Post-revolution Cuba has been characterized by significant levels of emigration, which has led to a large and influential diaspora community. During the three decades after January 1959, more than one million Cubans of all social classes—constituting 10% of the total population—emigrated to the United States, a proportion that matches the extent of emigration to the U.S. from the Caribbean as a whole during that period.[333][334][335][336][337] Prior to 13 January 2013, Cuban citizens could not travel abroad, leave or return to Cuba without first obtaining official permission along with applying for a government-issued passport and travel visa, which was often denied.[338] Those who left the country typically did so by sea, in small boats and fragile rafts.

On 9 September 1994, the U.S. and Cuban governments agreed that the U.S. would grant at least 20,000 visas annually in exchange for Cuba's pledge to prevent further unlawful departures on boats.[339]

In 2023, Cuba is undergoing its most severe socioeconomic crisis since the fall of the Soviet Union, leading to a record number of Cubans fleeing the island.[340] In 2022 alone, the number of Cubans trying to enter the United States, primarily through the Mexican border, surged from 39,000 in 2021 to over 224,000. Many have resorted to selling their homes at very low prices to afford one-way flights to Nicaragua, hoping to travel through Mexico to reach the U.S.[340] For those remaining among the island's 11 million inhabitants, life grows increasingly desperate. Internal migration has led to overpopulation in the capital, Havana, resulting in people living in makeshift shelters or overcrowded buildings, some of which are on the brink of collapse. The island's persistent shortages of food and medicine can be attributed to the U.S. trade embargo in place since 1962 and stringent government control over the economy since 1959. Regular power outages harken back to the early 1990s, a time when Soviet subsidies ended, plunging the island into economic hardship.[340]

Cuba's "Special Period" saw the country relying heavily on foreign tourism and the earnings of nationals working abroad. The pandemic, however, severely affected this revenue stream, decreasing the number of tourists by 75% in 2020. Monetary reforms in 2021 introduced shocks of inflation, further exacerbating the country's food scarcity and boosting the black market's prominence.[340] Despite the increasing hardships, the Cuban spirit remains resilient. Access to the internet since 2018 and widespread use of social media have fueled calls for political and economic liberalization. The power of the internet was evident during the Cuban protests of 2021, which were promptly suppressed by the police, with many prominent artists and bloggers detained.[340]

As of 2013 the top emigration destinations were the United States, Spain, Italy, Puerto Rico, and Mexico.[341] Following a tightening of U.S. sanctions and damage to the tourist industry by the COVID-19 pandemic, emigration has accelerated. In 2022, more than 2% of the population (almost 250,000 Cubans out of 11 million) migrated to the United States, and thousands more went to other countries, a number "larger than the 1980 Mariel boatlift and the 1994 Cuban rafter crisis combined", which were Cuba's previous largest migration events.[269]

Languages

The official language of Cuba is Spanish and the vast majority of Cubans speak it. Spanish as spoken in Cuba is known as Cuban Spanish and is a form of Caribbean Spanish. Lucumí, a dialect of the West African language Yoruba, is also used as a liturgical language by practitioners of Santería,[342] and so only as a second language.[343] Haitian Creole is the second-most spoken language in Cuba, and is spoken by Haitian immigrants and their descendants.[344] Other languages spoken by immigrants include Galician and Corsican.[345]

Religion

In 2010, the Pew Forum estimated that religious affiliation in Cuba is 59.2% Christian, 23% unaffiliated, 17.4% folk religion (such as santería), and the remaining 0.4% consisting of other religions.[346] In a 2015 survey sponsored by Univision, 44% of Cubans said they were not religious and 9% did not give an answer while only 34% said they were Christian.[347]

Cuba is officially a secular state. Religious freedom increased through the 1980s,[348] with the government amending the constitution in 1992 to drop the state's characterization as atheistic.[349]

Roman Catholicism is the largest religion, with its origins in Spanish colonization. Despite less than half of the population identifying as Catholics in 2006, it nonetheless remains the dominant faith.[279] Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI visited Cuba in 1998 and 2011, respectively, and Pope Francis visited Cuba in September 2015.[350][351] Prior to each papal visit, the Cuban government pardoned prisoners as a humanitarian gesture.[352][353]

The government's relaxation of restrictions on house churches in the 1990s led to an explosion of Pentecostalism, with some groups claiming as many as 100,000 members. However, Evangelical Protestant denominations, organized into the umbrella Cuban Council of Churches, remain much more vibrant and powerful.[354]

The religious landscape of Cuba is also strongly defined by syncretisms of various kinds. Christianity is often practiced in tandem with Santería, a mixture of Catholicism and mostly African faiths, which include a number of cults. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre (the Virgin of Cobre) is the Catholic patroness of Cuba, and a symbol of Cuban culture. In Santería, she has been syncretized with the goddess Oshun. A breakdown of the followers of Afro-Cuban religions showed that most practitioners of Palo Mayombe were black and dark brown-skinned, most practitioners of Vodú were medium brown and light brown-skinned, and most practitioners of Santeria were light brown and white-skinned.[355]

Cuba also hosts small communities of Jews (500 in 2012), Muslims, and members of the Baháʼí Faith.[356]

Several well-known Cuban religious figures have operated outside the island, including the humanitarian and author Jorge Armando Pérez.

Education

The University of Havana was founded in 1728 and there are a number of other well-established colleges and universities. In 1957, just before Castro came to power, the literacy rate was as low as fourth in the region at almost 80% according to the United Nations, yet higher than in Spain.[98] Castro created an entirely state-operated system and banned private institutions. School attendance is compulsory from ages six to the end of basic secondary education (normally at age 15), and all students, regardless of age or gender, wear school uniforms with the color denoting grade level. Primary education lasts for six years, secondary education is divided into basic and pre-university education.[357] Cuba's literacy rate of 99.8 percent[276][358] is the tenth-highest globally, largely due to the provision of free education at every level.[359] Cuba's high school graduation rate is 94 percent.[360]

Higher education is provided by universities, higher institutes, higher pedagogical institutes, and higher polytechnic institutes. The Cuban Ministry of Higher Education operates a distance education program that provides regular afternoon and evening courses in rural areas for agricultural workers. Education has a strong political and ideological emphasis, and students progressing to higher education are expected to have a commitment to the goals of Cuba.[357] Cuba has provided free education to foreign nationals from disadvantaged backgrounds at the Latin American School of Medicine.[361][362]

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are Universidad de la Habana (1680th worldwide), Instituto Superior Politécnico José Antonio Echeverría (2893rd) and the University of Santiago de Cuba (3831st).[363]

Health

After the revolution, Cuba established a free public health system.[26]