William Kissam Vanderbilt II

William Kissam Vanderbilt II | |

|---|---|

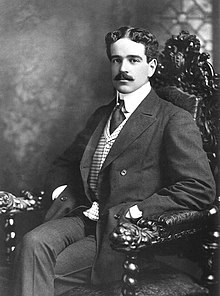

Vanderbilt photographed by Theodore C. Marceau, 1903 | |

| Born | October 26, 1878 New York City, US |

| Died | January 8, 1944 (aged 65) New York City, US |

| Burial place | Vanderbilt Family Cemetery and Mausoleum, Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

| Education | St. Mark's School Harvard University |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3, including Muriel Vanderbilt |

| Parent(s) | William Kissam Vanderbilt Alva Erskine Smith |

William Kissam Vanderbilt II (October 26, 1878 – January 8, 1944) was an American motor racing enthusiast and yachtsman, and a member of the prominent Vanderbilt family.

Early life

[edit]He was born on October 26, 1878, in New York City,[1] the second child and first son of William Kissam Vanderbilt and Alva Erskine Smith. His maternal grandfather was Murray Forbes Smith. Known as Willie K., he was a brother to Harold Stirling Vanderbilt and Consuelo Vanderbilt. Born to a life of luxury, he was raised in Vanderbilt mansions, traveled to Europe frequently, and sailed the globe on yachts owned by his father.

Willie was educated by tutors and at St. Mark's School. He attended Harvard University but dropped out after two years.

Career

[edit]While a great part of his life was filled with travel and leisure activities, Willie's father put him to work at the family's New York Central Railroad offices at Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan. As such, in 1905 he joined other Vanderbilts on Fifth Avenue, hiring the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to design a mansion at 666 Fifth Avenue.[2]

Already extremely wealthy from a trust fund and from his income as president of the New York Central Railroad Company, on his father's death in 1920 Willie inherited a multimillion-dollar fortune.

Life as an heir

[edit]Although he developed an interest in horse racing and yachting, he was particularly fascinated with automobiles. At age 10, during a stay in the south of France he had ridden in a steam-powered tricycle from Beaulieu-sur-Mer the 7 kilometers to Monte Carlo. As a twenty-year-old, in 1898 he ordered a French De Dion-Bouton motor tricycle and had it shipped to New York. Soon, he acquired other motorized vehicles and before long began to infuriate citizens and officials alike as he sped through the towns and villages of Long Island, New York, en route to Idle Hour, his parents' summer estate at Oakdale.

A skilled sailor, he took part in yacht racing, winning the Sir Thomas Lipton Cup in 1900 with his new 70-foot (21 m) sailing yacht he had named Virginia in honor of his new bride. In 1902, Vanderbilt began construction on his own country place at Lake Success on Long Island that he named "Deepdale." In 1903 he bought Tarantula, the first turbine-powered steam yacht in the World.[3]

However, sailing took second place to his enthusiasm for fast cars. In 1904, Willie set a new land speed record of 92.30 mph (148.54 km/h) in a Mercedes-Benz at the Daytona Beach Road Course at Ormond Beach, Florida. That same year, he launched the Vanderbilt Cup, the first major trophy in American auto racing. An international event, designed to spur American manufacturers into racing, the race's large cash prize drew the top drivers and their vehicles from across the Atlantic Ocean who had competed in Europe's Gordon Bennett Cup. Held at a course set out in Nassau County on Long Island, New York, the race drew large crowds hoping to see an American car defeat the mighty European vehicles. However, a French Panhard vehicle won the race and fans would have to wait until 1908 when 23-year-old George Robertson of Garden City, New York, became the first American to win the Vanderbilt Cup.

The Vanderbilt Cup auto races repeatedly had crowd control problems and at the 1906 race a spectator was killed. Seeing the potential to solve the safety issue as well as improve attendance to his race, and with encouragement from AAA official A. R. Pardington, Vanderbilt formed a corporation to build the Long Island Motor Parkway, one of the country's first modern paved parkways that could not only be used for the race but would open up Long Island for easy access and economic development.[4] Construction began in 1907 of the multimillion-dollar toll highway that was to run from the Kissena Corridor in Queens County over numerous bridges and overpasses to Lake Ronkonkoma, a distance of 48 miles (77 km). However, the toll road was never able to generate sustainable profits and in 1938 it was formally ceded to the county governments in lieu of the $80,000 due in back taxes.[4]

His new high-speed road complemented a train service that allowed a rapid exit from Manhattan. Becoming the first suburban automobile commuter, in 1910 Willie began work on the much more elaborate and costly "Eagle's Nest" estate at Centerport, Long Island. An avid collector of natural history and marine specimens as well as other anthropological objects, he traveled extensively aboard his yacht as well as overland to numerous destinations around the globe. He acquired a vast array of artifacts for his collection during his well-documented travels and after service with the United States Navy during World War I, he published a book titled "A Trip Through Sicily, Tunisia, Algeria, and Southern France." A few years later, he engaged William Belanske, an artist from the American Museum of Natural History to take part with him in a scientific voyage to the Galapagos Islands. By 1922, Vanderbilt had commissioned the construction of a single-story building on his Long Island estate to serve as a public museum, and less than a decade later a second story was added on to accommodate the growing collection.[5] William Belanske, who had accompanied Vanderbilt on his Galapagos voyage, was employed as the full-time curator of this museum.[6]

Military service

[edit]

In 1913, Vanderbilt traded in his steam turbine yacht Tarantula for a new motor yacht, also named Tarantula.[7][8][9] On May 9, 1917, the United States Navy commissioned the second Tarantula at Brooklyn Navy Yard as a patrol boat, with the hull number SP-124, and appointed Lieutenant Vanderbilt as its commander. The Navy chartered the yacht from him for the duration of the war. He was assigned to patrol duty in the waters of the 3rd Naval District, and escorted convoys in waters off New York and New Jersey. On October 1, 1917, he was released from active duty and given a temporary leave of absence to resume his duties of vice-president of the New York Central Railroad. A few months later, he was elected president of the New York Central Railroad and acted in this capacity for the remainder of the war.[10]

After the war, Vanderbilt was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve on May 17, 1921.[11] He remained in the Naval Reserve until he was transferred to the Honorary Retired List on January 1, 1941, for physical disability.[12]

Residences

[edit]In 1925, he traded the luxury yacht Eagle for ownership of Fisher Island, Florida, a place he used as a winter residence.[13] He built a mansion complete with docking facilities for his yacht, a seaplane hangar, tennis courts, swimming pool, and an eleven-hole golf course. This home was called Alva Base and the architect was Maurice Fatio.[14] In addition to this property, and his Long Island estate, Eagle's Nest, which was designed by Warren & Wetmore,[15] Vanderbilt also owned a farm in Tennessee and Kedgwick Lodge, a hunting lodge designed for his father by architect Stanford White, on the Restigouche River in New Brunswick, Canada.

Personal life

[edit]In 1899, Vanderbilt married Virginia Graham Fair (1875–1935), a wealthy heiress whose father, James Graham Fair, had made a fortune in mining the famous Comstock Lode. They spent their honeymoon at the Idle Hour estate but disaster struck when fire broke out and the mansion burned to the ground. Before their separation and divorce, Vanderbilt and his wife had a son and two daughters, the younger of whom was named for his sister:

- Muriel Vanderbilt (1900–1972), who married three times, the first in 1925 to Frederic Cameron Church, Jr. She later married Henry Delafield Phelps and John Payson Adams.

- Consuelo Vanderbilt (1903–2011)[16] who first married Earl E. T. Smith (1903-1991), the U.S. Ambassador to Cuba,[17] in 1926. They divorced in 1935 and she married to Henry Gassaway Davis III (1902-1984), who was and the grandson of Henry G. Davis and recently divorced from her cousin, Grace Vanderbilt.[18] They divorced in 1940 and she married William John Warburton III (1895-1979) in 1941. They divorced in 1946 and in 1951, she married Noble Clarkson Earl Jr. (1900–1969).[19]

- William Kissam Vanderbilt III (1907–1933), who inherited his father's love of fast cars and exotic travel, was killed in an automobile accident in South Carolina while driving home to New York City from his father's Florida estate.

The Vanderbilts separated after ten years of marriage but did not formally divorce until 1927 when he wanted to remarry. Divorce proceedings were handled by his New York lawyers while he and Rosamund Lancaster Warburton (1897–1947), a former wife of Barclay Harding Warburton II and an heir to the John Wanamaker department store fortune, waited discreetly away from the media at a home in the Parisian suburb of Passy, France. When the divorce was final, the couple were married at the Hotel de Ville (city hall) in Paris on September 5, 1927. Vanderbilt became a legal stepfather to Barclay Harding Warburton III once they wed.

Vanderbilt died on January 8, 1944, of a heart ailment.[20] He was interred in the Vanderbilt Family Cemetery and Mausoleum on Staten Island, New York.[21][22] His estate was valued at $35,815,614, from which approximately $18,844,000 in Federal Estate Taxes and $5,600,000 in New York Estate taxes were deducted.[23]

Legacy

[edit]In 1931, Vanderbilt had the Krupp Germaniawerft in Kiel, Germany, build for him the 264-foot diesel yacht Alva. The Alva was donated by Vanderbilt to the U.S. Navy on November 4, 1941. The Alva was converted to a gunboat and commissioned as the USS Plymouth (PG-57) on December 29, 1941. The Plymouth was primarily employed as a convoy escort on the East Coast and in the Caribbean and was sunk by a torpedo from a German U-boat on August 5, 1943, at 21.39 with the loss of 95.

By the 1940s, Vanderbilt had organized his will so that, upon his death, the Eagle's Nest property along with a $2 million upkeep fund would be given to Suffolk County, New York, to serve as a public museum. Since 1950, the site has operated as the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum.[24]

References

[edit]- ^ Gittelman, Steven H. (2010). Willie K. Vanderbilt II: A Biography. McFarland. p. 12. ISBN 9780786458233. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Howard Kroplick (December 29, 2015). "Willie K. and Virginia Vanderbilt's Mansion at 666 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan". Vanderbilt Cup Races. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ^ "Howard Gould's steam yacht the winner". The New York Times. September 29, 1904. p. 7 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b Burns, John M. (2006). Thunder at Sunrise: A History of the Vanderbilt Cup, the Grand Prize and the Indianapolis 500, 1904-1916. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-7864-7712-8.

- ^ "History of the Vanderbilt Museum | Historic Mansion Long Island".

- ^ "Exhibit Opens: Artist-Curator William Belanske". October 24, 2015.

- ^ "New Vanderbilt yacht". The New York Times. November 11, 1912. p. 1 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Vanderbilt boat building". New-York Tribune. December 2, 1912. p. 9 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Register of Yachts. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914. TAR – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Harvard's Military Record in the World War. pg. 983.

- ^ Register of Commissioned Officers of the U.S. Naval Reserve. July 1, 1939. pg. 3.

- ^ Register of Commissioned Officers of the U.S. Naval Reserve. July 1, 1941. pg. 488.

- ^ Fisher, Lionel L. Fisher Island. Fisher Island, FL: Island Developers, 1994. p. 18.

- ^ Mockler, Kim. Maurice Fatio: Palm Beach Architect. New York: Acanthus Press, 2010. ISBN 0-926494-09-0. p. 196.

- ^ "At Long Island's Historic Vanderbilt Mansion, Eagle's Nest". Untapped New York.

- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths EARL, CONSUELO VANDERBILT". The New York Times. February 25, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "Members of Leading Families Attend Service for Mrs. Balsan". The New York Times. December 10, 1964. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "TROTH ANNOUNCED OF MRS. G.V. SMITH; Daughter of Win. K. Vanderbilt Affianced to H. G. Davis 3d, Ex-Husband of Cousin. GRANDSON OF A SENATOR Ceremony to Take Place Friday at Florida Estate of Father of Prospective Bride". The New York Times. November 26, 1936. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ Shapiro, T. Rees (February 25, 2011). "Consuelo Vanderbilt Earl, heiress, dog breeder and link to golden age, dies at 107". Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "W. K. VANDERBILT DIES IN HOME HERE; Founder of the Vanderbilt Cup. Races -- Former President of New York Central". The New York Times. January 8, 1944. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- ^ "William Kissam Vanderbilt". Associated Press. January 8, 1944. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "W. K. Vanderbilt Dies In N. Y. Of Heart Disease". Chicago Tribune. January 8, 1944. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2011.

- ^ Newsday (Suffolk Edition). (30 September 1947, Page 45). Estate of Mrs Rosamond Lancaster Vanderbilt. Newspapers.com. Retrieved 11 January 2025, from https://www.newspapers.com/article/newsday-suffolk-edition-estate-of-mrs/162764944/, accessed 11 January 2025.

- ^ "History of the Vanderbilt Museum | Historic Mansion Long Island".

External links

[edit]- William K. Vanderbilt Jr. (VanderbiltCupRaces.com)

- 1878 births

- 1944 deaths

- 20th-century American railroad executives

- American male sailors (sport)

- Vanderbilt family

- Harvard University alumni

- Land speed record people

- American people of Dutch descent

- St. Mark's School (Massachusetts) alumni

- Racing drivers from New York City

- People from Centerport, New York

- People from Lake Success, New York

- Trust Company of America people

- Former yacht owners of New York City

- Burials at the Vanderbilt Family Cemetery and Mausoleum